No sex please, we're physiotherapists

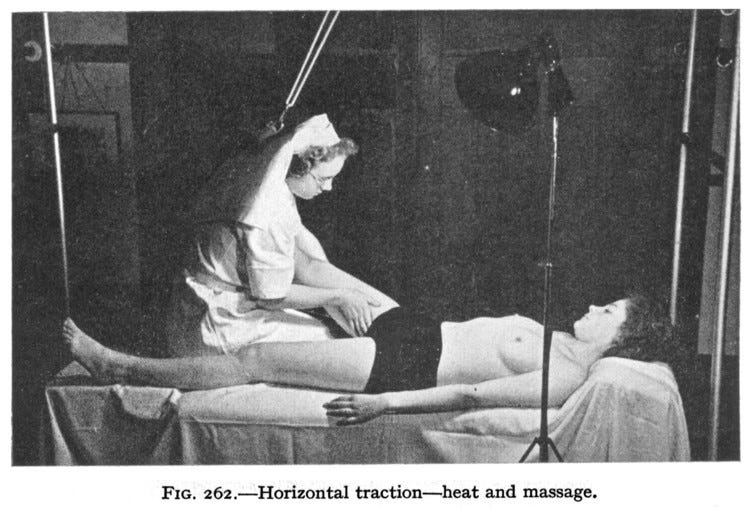

from Guthrie-Smith O. (1952, p403) The physiotherapy profession has a rather odd relationship with sex and sensuality. On the one hand, it lies at the heart of everything that physiotherapists do, on the other it is almost completely invisibly; un-theorized, glanced over in graduate programmes, and almost invisible in models that try to explain what physiotherapy is and isn't. Over the course of the next few blogposts, I want to tackle some of the issues that surround sex and physiotherapy and see if we can't develop a more mature appreciation for it's everyday role in defining our professional subjectivity. To begin with, we should acknowledge the role that sex played in the formation of the physiotherapy profession. The physiotherapy profession as we know it today, began when four young nurses and midwives formed the Society of Trained Masseuses in the summer of 1894 in response to what the British Medical Journal called the Massage Scandals (BMJ, 1894). Massage had become extremely popular, especially among the affluent classes in the large towns and cities of Europe and North America. Unfortunately, it's popularity meant that it attracted all manner of practitioners, many of whom were self taught, or had received only the briefest training. It was possible for a masseur or masseuse (the gender differentiation is significant here), to obtain a certificate from a doctor or training school after only half a day's study, and so it became increasingly difficult to distinguish who was a legitimate practitioner and who was a quack. Worse still, massage became known as a way for brothels to avoid being closed down by police, which led many legitimate masseuses to despair that they would always be confused with prostitutes. Well paid, reliable work was hard to come by and there was no efficient way to convince the government of the day, the medical profession, or the public that massage could be performed without impropriety. The Massage Scandals forced a small group of young nurses and midwives to form the Society of Trained Masseuses (STM), and their singular purpose was to make massage 'a safe, clean and honourable profession, and it shall be a profession for British women’ (Grafton, 1934 p.229). In other words, they had to find a way to show that it was possible to touch people - sometimes in quite intimate and private ways - without any accusation of licentiousness. How they did this was both fascinating, brilliant and profoundly influential in the history of the physiotherapy profession (for a more detailed account, see Nicholls & Cheek, 2006; Nicholls & Gibson, 2010). The founders of the STM - the organisation that would be the progenitor of most physiotherapy professional bodies around the world - did four radically important things; each one designed to restrain the sensual nature of massage practice:

They only trained women. For the first 20 years, no men could register as STM members or gain access to patients.

They only treated women. Prior to WWI, men could be treated but only rarely, and under the strictest medical conditions

They aggressively promoted the medical view that the body should be treated as a machine - thus securing the trust of many doctors and guiding tutors to train their students to see 'body' parts not 'private' parts (apologies, I couldn't resist this pun.)

They only allowed people to register and gain access to medical referrals if they passed the Society's examination, which focused on the twin disciplines of their biomechanical view of the body, and the Society's highly moral code.

What these steps were brilliantly effective in doing, was distancing the profession from scandal, and giving practitioners a de-sensualized view of the body that would be reassuring to the practitioner, the doctor and the patient. What they were not able to do, however, was completely remove sensuality from the experience of touch - a problem that has always, and will always remain for those who use intimate forms of touch in their practice:

Many of us are led to this work (massage) for high-minded reasons. For most, there’s a wish to bring greater ease into the lives of others. Some even see this work as a sacred calling, a way to heal the soul and enliven the spirit. But despite the good intentions we bring to our sessions, because we’re working closely with the physical body, we can’t avoid the murkiness and confusion of sexual issues (McKintosh, 2005, p. 100).

The sensuality of touch cannot be avoided. We might choose to manage it and regulate it, but it cannot be entirely effaced. This, then, creates an enduring problem for anyone who practices touch-based therapy. Speaking specifically about physiotherapy, it might be argued that the profession has benefited hugely from our legitimate and orthodox history, and maybe this explains why sex and sensuality are so rarely discussed within the profession. But equally, there may be things that physiotherapists are not able to do because of their highly regulated approach to sex and sensuality, and these things may be becoming increasingly important as people demand more from their professional practitioner than a technician who views their body as a machine (see, Nicholls and Holmes, 2012). Some have argued that physiotherapy's over-regulated approach to touch is now getting in the way of a more holistic engagement with people and the full sensuality of massage:

...the term “massage,” alas, still seems to be tainted in many quarters by its common associations with touchy-feely parlors, and even with disguised prostitution. This is an unfortunate situation, and one that is unfair to a large number of legitimate practitioners... It is not that I sternly deplore touchy-feely. In a culture that is as starved for touch as ours, I suspect there may be some healthful benefits to pleasant tactile stimulations in almost any form whatever. But in order to discuss the kind of bodywork I mean, I strongly feel the need for a word [other than massage] that in no way implies contact that is merely sensual, or that is sexual in any shape or form (next paragraph follows).

...The term “physical therapy” avoids these associations, but it is too narrow in the scope of its normal use. It refers to an official medical discipline, one which is licensed only after protracted and highly specific studies, prescribed only by physicians, and applied through fixed procedures. Such academic rigor certainly does not count against it as a responsible therapeutic practice, but it does effectively partition “physical therapy” off form many other useful kinds of touching and manipulation. In particular, it typically eliminates a good deal of the intuitive element which seems to be such an important part of other approaches and which is fact many physical therapists have confessed to me that they wish they could use more freely in the clinical practice (Juhan, p.xx).

Clearly this is a topic that needs much more open, honest and thoughtful discussion, because it may well be an important part of the profession's reform. References

British Medical Journal. (1894). Astounding revelations concerning supposed massage houses or pandemoniums of vice, frequented by both sexes, being a complete expose of the ways of professed masseurs and masseuses (pp. 3-15). Wellcome Institute Library, London, Ref. SA/CSP/P.1/2: British Medical Association.

Grafton, S.A. (1934). The history of the Chartered Society of Massage and Medical Gymnastics, JCSMMG, March, 229.

Guthrie Smith, O. F. (1952). Rehabilitation, re-education and remedial exercise. London: Bailliere, Tindall & Cox.

Juhan, D. (1987). Job’s body: A handbook for bodywork. New York: Station Hill Press.

McIntosh, N. (2005). The educated heart: Professional boundaries for massage therapists, bodyworkers, and movement therapists. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins.

Nicholls, D. A., & Cheek, J. (2006). Physiotherapy and the shadow of prostitution: The society of trained masseuses and the massage scandals of 1894. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 62(9), 2336-2348. doi:doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.09.010.

Nicholls, D. A., & Gibson, B. E. (2010). The body and physiotherapy. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice, 26(8), 497–509. doi:10.3109/09593981003710316.

Nicholls, D. A., & Holmes, D. (2012). Discipline, desire, and transgression in physiotherapy practice. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice, 28(6), 454-465. doi:10.3109/09593985.2012.676940.